Searching for the Dutch-Paris Escape Line

Wartime Railway Journeys

If you were to trace the steps of Dutch-Paris couriers and guides, you would do most of it by train. Like all civilians during the occupation, they relied on the railway to get themselves and those they were helping from one city to another. So you could get on a train in Amsterdam and follow the same route as an Engelandvaarder to Toulouse.

But you could not entirely re-create the journey. Obviously, Europe is not at war and who would really want to experience the anxiety of Gestapo identity checks and possible air raids? But there are more peaceable differences between then and now as well.

The European Union has abolished the international border crossings, so you no longer have to get off the train, shuffle through customs and passport control, and get back on the train when leaving one country and entering another.

There are also fewer trains now than there were in 1944. Belgium had an impressively dense network of trains and tram, many of which have been replaced by roads for automobiles. Likewise, many of the current roads in the Pyrenees were train tracks in 1944.

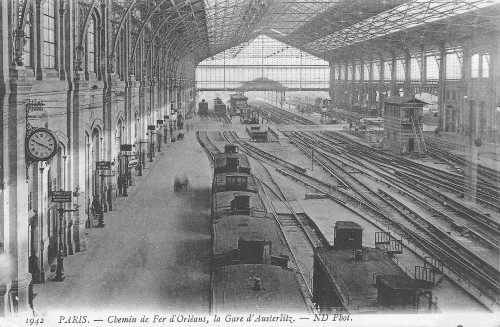

The trains themselves were different as well, as you can see in this postcard of the Gare d’Austerlitz in Paris.  Many of them had first, second and third class carriages. Only the most modern of them had the connecting carriages that we take for granted today. The upside of the old-fashioned trains in which you had to get off the train altogether and walk along the platform to get into the next carriage, was that the German police didn’t much care for them. At least in the Pyrenees, they preferred the modern trains with carriages that they could walk between while the train was in motion and rarely controlled passports in the old fashioned trains.

Many of them had first, second and third class carriages. Only the most modern of them had the connecting carriages that we take for granted today. The upside of the old-fashioned trains in which you had to get off the train altogether and walk along the platform to get into the next carriage, was that the German police didn’t much care for them. At least in the Pyrenees, they preferred the modern trains with carriages that they could walk between while the train was in motion and rarely controlled passports in the old fashioned trains.

Wartime trains were also big polluters, billowing out huge clouds of steam laden with coal dust. Today you need to visit a railway museum to smell that particular combination of hot, damp coal and metal. The steam of the trains created its own atmosphere in the train stations as well as causing continual negotiations among passengers about opening or shutting the windows. Closing them kept out the soot. Opening them allowed for the possibility of some air as well as lessening the impact of any possible explosions. None of the trains, even the most modern, had air conditioning.

In fact, compared to today’s high speed, international train travel, even the most uneventful first class train journey during the occupation was slow, inconvenient and uncomfortable. But it was the best available and the men and women of Dutch-Paris relied on it.

- Tags: Border Crossings

Leave a reply