Searching for the Dutch-Paris Escape Line

A friend of mine mentioned that the blog is very interesting but I’d neglected to write about how critical a role luck played in escaping Nazi Europe. He should know because he’s an Engelandvaarder who traveled from Amsterdam to Spain via Dutch-Paris. He now lives in Tasmania and has quite convinced me to move there if I should ever have the means, but that’s another story.

My friend, we’ll call him Z, generously shared his as-yet unpublished memoir of his escape with me. I hope it is published because not only is it the kind of story that will keep you turning pages until all hours, but it will teach you a lot about life in Occupied Europe. I’m willing to bet that none of you knew that one of the best places for a man of military age to hide in Amsterdam was the golf club. Apparently the Germans didn’t think they’d catch enough evaders there to make it worth their while to raid it.

It’s no coincidence that Z calls his memoir Luck Through Adversity. I’ll give you just three examples from it of the kind of luck you needed to stay away from the firing squad.

(1) On Z’s first attempt to get to England, his escape-line contact in Breda (the Netherlands) received a warning that stopped Z from crossing the border a few hours later. Members of the escape line had been arrested in Brussels, turning Z’s destination there into a trap.

(2) On his second attempt, Z was arrested because of indiscretions during a night out in Paris. That was unlucky. But it turned out that the Germans who arrested him didn’t know Paris well enough to navigate in the black-out. For two or three seconds all three Germans turned to the left to try to read a street sign. That was lucky because it allowed Z to roll out of the Citroën and get away. (Of course that was only lucky because Z had the audacity to let himself out of the Wehrmacht vehicle and could run so fast, but he gives the credit to luck).

(3) That arrest and escape in Paris convinced the Dutch-Paris agents to put Z and his companion on the Line down to Toulouse ahead of schedule. The two of them crossed the Pyrenees without notable difficulty and even managed to get through Spain without the usual purgatory in one of the Spanish internment camps. That was lucky because they were supposed to travel south with a convoy that ran into a German ambush at the Col de Portet d’Aspet eleven days after they had passed through it. Many of the men in his original group perished on the mountainside or in a concentration camp.

There are other less dire examples of luck in the story, but these will show you how crucial it could be. They also demonstrate that along with luck you needed the wit to take advantage of it. And they remind us that this wasn’t a game. Some people were lucky and they got through, but others were unlucky. And they died.

From Where the World Is Run

In my off minutes from being an historian or mommy, I’ve been reading Hilary Mantel’s Booker Prize winning novel Wolf Hall. I’ve been surprised to discover that St. Thomas More personally oversaw the torture of heretics while Thomas Cromwell made sure his kitchen boys were warmly dressed and taught to read and write. But what resonated most thoroughly with me was the following quotation:

“The world is not run from where he [Henry VIII] thinks. Not from his border fortresses, not even from Whitehall. The world is run from Antwerp, from Florence, from places he has never imagined; from Lisbon, from where the ships with sails of silk drift west and are burned up in the sun. Not from castle walls, but from counting houses, not by the call of the bugle but by the click of the abacus, not by the grate and click of the mechanism of the gun but by the scrape of the pen on the page of the promissory note that pays for the gun and the gunsmith and the powder and shot.”

That is true for Dutch-Paris. Every member of the Line counts as a hero. But heroism wasn’t enough. If Dutch-Paris didn’t need promissory notes for guns they needed them for food and train tickets and false documents. The entire enterprise relied on a network of bankers, professional or metaphorical who raised money and clicked their abacuses to get the best exchange rates, to marshal their funds, to make their efforts cost-effective.

In August 1944, Dutch-Paris was supporting 400 people at 150 addresses in and around Brussels at the cost of 400,000 Belgian francs for that month alone and not including the costs of their information and people-smuggling operations in the other four countries involved. Not one centime of that was spent legally but it all had to be spent in cash. Donations came in Dutch guilders, Swiss francs, and Belgian francs with the occasional contribution of US dollars, Pounds sterling and Canadian dollars. There were undoubtedly some Australian dollars and other unlikely currencies involved as well.

Money did not flow freely in Hitler’s New Order. In fact, the Germans had a special currency police to make sure that it did not. And yet it did, from places that the men with the guns probably did not even imagine.

For example, when the donations of private individuals proved insufficient, the Comité tot Steun van Nederlandse Oorlogsslachtoffers in België requested funds from the Dutch government-in-exile. London sent them in the form of a microfilmed promissory note drawn on Swiss francs that was smuggled from Switzerland to Brussels in an empty fountain pen. The Comité then raised substantial loans among the Dutch community in Belgium on the strength of a microfilmed letter from an exiled government. One of the Comité‘s members, a bank director, also created a system of false accounts to draw the Swiss francs directly from Switzerland and exchange them into Belgian francs before distributing them through a series of false checks.

Dutch businessmen in their forties who lived in Belgium created exchange loops with their business associates or their relatives living in the Netherlands. They recruited a cheese dealer who had the legal right to exchange guilders for francs at the best possible rate, that of the Brussels bourse.

The bankers gave the money to the couriers, who gave it to the forgers and the passeurs and the shopkeepers who would sell potatoes or shoes without ration tickets. And they kept the Jewish families alive and they snuck the pilots and the journalists and the priests and the young men who were going to London to bring down the Third Reich out of Occupied Europe to the Allies’ bases in England. Despite the enemy’s guns and despite his fortifications.

Let us pause for a moment on this 91st anniversary of the Armistice that halted the official slaughters of the First World War (1914-1918) to remember the men and women who have died in our battles over the last century and those who’ve lived the rest of their lives under the shadow of those battles.

It would take an entire semester to work out all that that first war unleashed – some good (female suffrage), most bad (Spanish Flu pandemic). The most notorious consequence, of course, was the Second World War (1939-1945).

Now that was a war that did not limit itself to the military for either fighters or victims. That was a war that compelled soldiers and civilians alike to great acts of courage. So among today’s photos of Marines at Iwo Jima, half-frozen snipers at Stalingrad and French girls kissing their American liberators, I’d like to add another.

Taken in January 1944, it shows a Dutch-Paris “convoy” on the final stage of its journey out of Occupied Europe: climbing the Pyrenees. To my knowledge, the photo shows the French guide (a member of Dutch-Paris); a Dutch priest; two American airmen (one from Boston and the other, a boxer, from California); a Polish RAF Spitfire pilot; a Dutch lawyer and a Dutch intelligence agent. The others are probably Read the rest of this entry »

Following my last post about joining the Resistance, I’ll be offering a series of examples of how members of Dutch-Paris ended up in the Line. We’ll start with the chef de reseau himself,John Henry Weidner (1912-1994).

Weidner’s father was a Dutch Seventh Day Adventist preacher who taught at the SDA college at Collonges sur Salève, France, when John was still in school. That gave John a strict moral upbringing, fluency in French as well as Dutch, and personal knowledge of the Franco-Swiss border where he spent as much time mountain-climbing as he could. When the Wehrmacht invaded France in 1940, Weidner was a businessman and youth group leader in Paris. He and a French friend tried to get to England but missed the last boat. So the two of them opened a textile shop in Lyon, which, if nothing else, gave them an officially acceptable reason to travel. Read the rest of this entry »

How to Join the Resistance

Say it’s 1943 and you’ve had enough of the Occupier and his brutal ways. You know there’s a Resistance because you’ve read the illegal press and you’ve heard the rumors. You want to join, but how? It’s not like you can walk down to the local recruiting office or look them up in the phone book to make an appointment.

How did you join before the Allies landed in Normandy and the Resistance came out into the open? Read the rest of this entry »

- 0 Comments

- Tags: arrests, The Netherlands

Illegible Dutch Handwriting

It’s hard enough to read someone else’s handwriting in your native language, let alone in one you learned in graduate school. But to my immense relief, most of the documents I’ve come across so far are typed. In some cases that’s because somebody’s secretary typed up copies of handwritten reports (thank you!). But in other cases people typed their own reports or letters. It surprises me how many businesses and individuals still had their own typewriters just after the war. I wonder if people hid them from the Germans the same way they hid their radios and their bicycles.

But not everyone used a typewriter, and not everyone wrote legibly. I give you Exhibit A, a letter written to John Read the rest of this entry »

- 0 Comments

- Tags: Belgium, concentration camps

And in Box Number Three…..

The herculean task of organizing the Weidner Archives is being ably undertaken by Stan Tozeski, a retired archivist from NARA. He tells me that when he started in on a heap of moving boxes filled with manila folders and papers in various states of deterioration, in other words, the contents of John Henry Weidner’s office shipped across the country.

Weidner’s personal correspondence is now neatly alphabetized in acid-free folders and stacked in 36 (at my last count) archival-quality document boxes. Read the rest of this entry »

- 0 Comments

- Tags: Belgium, France

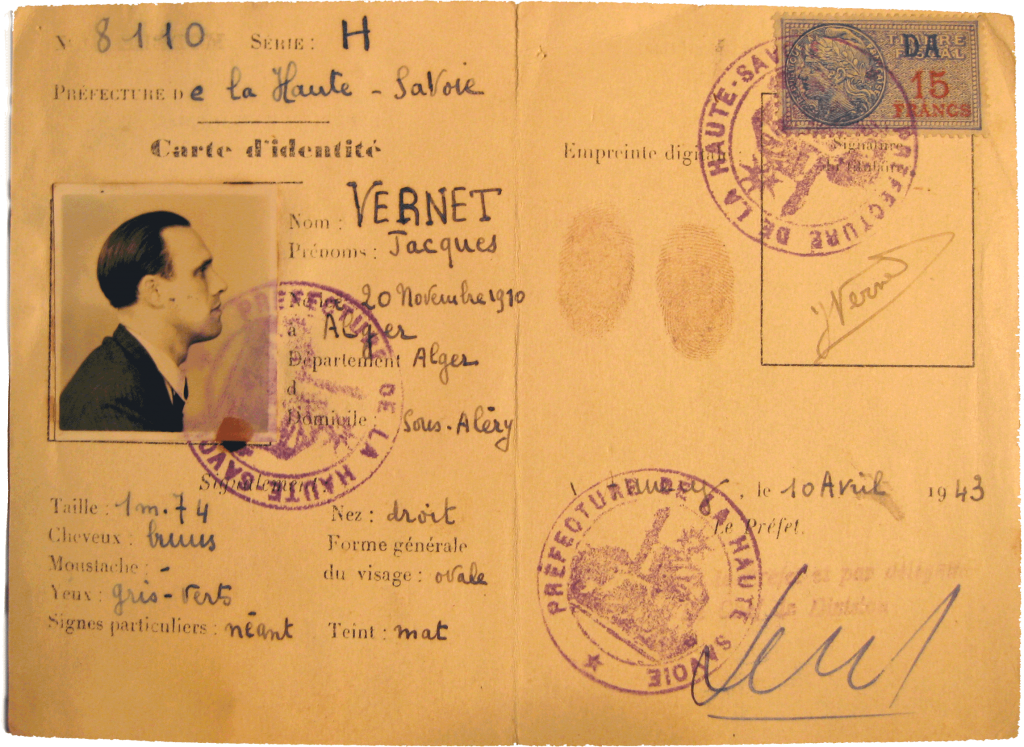

Whose Identity Card?

Travel papers such as the authorization to cross the borders of Haute-Savoie in the last blog would be easy enough to forge if you had the forms and the stamps. Identity cards posed more of a problem. Actually, they were more like identity booklets of heavy paper stock folded in thirds than the laminated cards Americans carry today in the form of driver’s licenses. That’s probably why the police agents in black and white movies are always saying: “your papers please.”

Dutch identity cards were notoriously difficult to forge because of the misplaced zeal of a civil servant who came up with a new way to complicate the cards and presented the idea to the occupying authority. The Belgians, however, had been through a nasty occupation during the First World War and had a deliberately simple, i.e. easily forged, identity card.

Take a good look at the following five identity cards, three French and two Belgian.

Issued to: Jacques Vernet, born 20 November 1910 in Algiers [Algeria, then a French territory]

Issued by: Prefecture of Haute-Savoie, 10 April 1943 Read the rest of this entry »

- 0 Comments

- Tags: Belgium, France, John Henry Weidner

Authorization to Leave the Haute-Savoie

In amongst the documentary riches of the Weidner Archive, I’ve found a little cache of false documents. Some of them are the fakes that John Henry Weidner himself used during the Occupation and the quite legitimate military documents issued to him at the liberation and just after the war. And some of them are the blank forms for said documents. Legally, only the issuing authority should have had those blank forms and the stamps that formalized them, but there was a brisk trade in them during the Occupation.

By the end of the war, the Dutch Resistance had a catalog of false documents. You told your contact what documents you needed, handed over some photographs, and three days later you had your papers. Read the rest of this entry »

It’s a Treasure Trove

Ladies and gentlemen, I stand corrected. It turns out that resisters did write a lot down. It’s just that they wrote it down after the danger had passed. For France that happened with the Liberation in the summer of 1944. Belgium was liberated in September 1944, as was a southern swathe of the Netherlands. To its immense sorrow, the northern majority of the Netherlands was not liberated until May 1945.

I am working in the Weidner Center Archives at Atlantic Union College in South Lancaster, Massachusetts. It holds Weidner’s private papers and a filing cabinet Read the rest of this entry »