Searching for the Dutch-Paris Escape Line

Random Violence Admist General Chaos

France fell apart under the onslaught of the Normandy Landings. Communications and transportation lines were broken throughout the country as the Resistance did its best to sabotage the German response to the invasion. Although some parts of the country passed the summer of 1944 peacefully enough, the region of the Alps along the Swiss border was boiling with a brutal sort of guerrilla warfare between the Germans and their collaborators and the maquisards of the Resistance. There was a such a high level of random violence in western Europe during the summer of 1944 that it made it almost impossible for organized, clandestine networks to operate.

On the 7th of July 1944, two of John Weidner’s lieutenants, we’ll call them Jacques and Armand, left the safety of Switzerland to find out what was happening to the rest of Dutch-Paris. They had heard disturbing rumors about Brussels and had lost track of one of their colleagues, Mouen.

They took their bikes with them, crossing through the frontier near St-Julien and riding from one Dutch-Paris safe house to another on the way to Annecy to gather the news. In Annecy they took a train that had to take a circuitous route to Lyon, stopping at St-Andre-le-Gaz. The night before the maquis had occupied the village and blown a train. That morning the Germans took the first thirteen young men they could lay their hands on and shot them in reprisal. They were still terrorizing the town when the train pulled through.

Our men arrived in Lyon at 10:00 pm on the 8th of July and went directly to the usual restaurant, but no one there had any news of Mouen other than a guess that he’d gone to Toulouse. They spent Sunday fruitlessly trying to contact various people and then took a train to Paris on Monday.

In Paris they found out that Mouen had definitely been there on June 30, but without Paul, and that several of their friends had been arrested. They also found out that it was impossible to get a train any further north than Nancy. They tried that, but after going 15 km in 3 hours and hearing that Nancy was heavily occupied, they returned to Paris.

Again, they tried to find a Dutch-Paris colleague who also worked for the Dutch Red Cross. When they finally did, it was only to learn of more arrests and several deportations of Dutch-Paris people to the concentration camps. It was the last time they would ever see him because he was arrested himself six days later, leading to his death in Buchenwald.

On the 13th of July our men boarded a train back to Lyon. After a long day during which the tedium was interrupted by three aerial attacks on the train, they arrived in Dijon only to be told that the rail lines to Lyon had been destroyed. The train kept moving slowly through the night, but could go no further than Chalons. There they joined up with three other men to hire a taxi to Lyon. The taxi driver was jittery and told them a long story about how another taxi driver had been summarily shot because one of his passengers had a weapon.

They set out on the 14th of July, the national holiday of the French Republic, with tricolor flags flying along the roads. But outside of Tournous they ran into a roadblock. All would have been OK if a plainclothesman at the road block hadn’t told the soldiers to search the taxi. They found some ammunition.

Suddenly there was shouting, rifle butts were being slammed into everyone who was in the taxi and they were all marched into a nearby home turned into a German HQ. The men were pushed up against the wall with great brutality and told to keep their arms high.

After a couple of hours like this they were called in for interrogation. Jacques was asked about some ration coupons that had been found in the car. Fortunately, his false documents had him as a police inspector so he was able to use that to make up a convincing story for himself and Armand, who he claimed was his superior. Three hours later the two of them were marched out of the house and behind a building, where their German guards shot into the air to scare the others and then told them to run. They considered themselves lucky to have escaped and been able to take a few of their possessions with them because “these “messieurs” were great thieves.”

A few hours later these same “messieurs” passed them in their new vehicle (the stolen taxi) and gave our men a ride to a town from which they managed to get a train to Lyon. They spent two days there trying to get news of Mouen and leaving messages for him, then left for Switzerland on the 17th. It took them three days of zig-zagging train routes and occasional mountainous bike rides to get back to the Swiss border. Once there a woman fed them and took them to the crossing point, only to see a German patrol in the nick of time. They tried again a few hours later and made it.

Jacques considered the mission to be a failure, but remarked that they had had more luck than most. He was right. The Paul who hadn’t been with Mouen in Paris had been caught up in a general razzia in Belgium in June and was deported to Germany as slave labor until the Allies liberated him the following spring.

- 0 Comments

- Tags: arrests, Belgium, Border Crossings, France

This Saturday morning, 16 July, the cyclists of the Tour de France will be pedaling past a lieu de mémoire (memory site) of Dutch-Paris: the Col de Portet d’Aspet. This 1,069 m pass is part of the St. Gaudens stage of the race. Sixty-seven years ago it was a stopping place on the route that Engelandvaarders and Allied airmen took as they walked over the Pyrenees to join the Allied armies.

It wasn’t an easy walk either, with inadequate footgear, only the food in your pockets and the Gestapo and German border guards on your heels. Things could go wrong, as they did on the cold morning of 6 February 1944.

There are, of course, various versions of the story; I’ll tell you what happened from the perspective of a 23 year-old American retail clerk who had been shot down over the Netherlands on his first mission as a B-17 radio operator.

Our aviator left Paris for Toulouse with 10 other airmen and three girls working for Dutch-Paris on 4 February. The next afternoon they took the train from Toulouse to Cazères. From there eight of them took a taxi and the rest took a bus to a village 10 or 15 miles further into the hills. They later learned that so many men with bags getting out of a taxi was noticed in the village and duly noted in the mayor’s regular report on strangers. According to our American the mayor was a good guy and didn’t expect the Germans to read his reports. But they did, and they sent a message to the border patrol. At dark the Americans got back into the taxi and rode to the foot of the mountains. There they met some Dutchmen and an Australian they’d known in Paris.

At 22:00 on 5 February 1944, the group of 24 Dutch Engelandvaarders and Allied airmen started along the trail with two guides. It started to snow on the second mountain, adding to the three feet of snow already there. At daybreak on 6 February they stopped in what our aviator called a deserted farmhouse for breakfast and a rest. About two hours later they left the hut – guides first then aviators, then Dutchmen – but the sun was low and in their eyes so they couldn’t see the German or his dog. When the lead guide started waving his hat, half the men apparently thought it meant to go back into the building. The others scattered up the hillside, making as many trails as possible in the snow. The Germans opened fire.

From behind a bush on the mountainside, our aviator saw 10 Germans on skiis surround the hut and put the 14 men inside it into a bus, which told him that the Germans had been expecting the round-up. Eight of those were Dutchmen between the ages of 19 and 32. Two of them later escaped in Toulouse and made it over the Pyrenees and on to London. But the other six were deported to the concentration camps. None of them survived.

Our American spent the next week hiding in a hut belonging to the guide’s fiancee’s father, then returned to Toulouse and was put into another Dutch-Paris convoy of Americans and Dutchmen. Heavy snowfall delayed their crossing the Spanish border until 19 March.

If you’re ever at the Col de Portet d’Aspet and not running a race or running for your life, you can visit part of the mountain hut where the Germans surrounded the escapees, now the historic site known as the “Cabane des évadés, Site classé, Février 1944,” and remember the men who almost made it to freedom.

And Another Way to Get Out of Switzerland

After a few days of meetings at the Dutch embassy in Bern, the Swiss secret service escorted Weidner and Felix back to the French border.* At a certain place the Swiss helped hold up the barbed wire so that Weidner, Felix and an unknown woman who apparently belonged to the Swiss Intelligence Service could crawl through the mud underneath it. Once on the road, the woman took Felix’s arm so that they were strolling along like silent lovers. Weidner sauntered in front of them until he suddenly ducked into a house, followed by the other two. Soon after, the German border patrol roared past on motorcycles and trucks with their helmets on.

It appeared to be the home of the French police inspector who had helped Weidner and Felix get into Switzerland. The inspector’s wife cleaned the mud off their clothes and gave them a warm cup of ersatz coffee, which, Felix later commented, was a sure sign that they were back in occupied France.

The rest of the journey was ordinary enough by the standards of the time that Felix Read the rest of this entry »

- 0 Comments

- Tags: Border Crossings, France, Switzerland, women

That’s One Way to Get Into Switzerland

In November 1943, John Weidner escorted the Dutch consular official who acted as the chief of the Paris section of Dutch-Paris to Switzerland. We’ll call him Felix. Felix was important enough that he got the VIP treatment, meaning that he travelled by himself rather than in a group and was personally accompanied all the way into Switzerland with the connivance of the Swiss authorities.

The two resisters took a train from Paris to Annecy and then another train to Chambery. That’s hardly the direct route between Annecy and Geneva, but it was the one favored by Dutch-Paris, suggesting that it was the only one available or the safest one at the time. Weidner spoke to an old man on the platform at Chambery then led Felix to a small shop. They went in the front, stopped in a small room for a snack and disappeared out the back door. In the meantime the old man arranged a Red Cross ambulance. Felix sat in front next to the driver and Weidner lay down in the back with several microfilms hidden beneath him, ready to show all the signs of acute appendicitis.

When they came to the customs border 5,000m before the international border, Read the rest of this entry »

- 0 Comments

- Tags: Border Crossings, France, Switzerland

To my surprise and delight, I’ve found the reports of the regular journeys that a Dutch-Paris courier made from Switzerland to France and Belgium every two weeks between October 1943 and June 1944. Our man was combining Dutch-Paris business with official Dutch government-in-exile business, which is why he typed reports. Of course, they were kept in Switzerland or they would never have been written in the first place. Even so, he used code names because there were spies everywhere, especially in Switzerland.

The reports concern meetings with various people, the delivery or non-delivery of microfilms, arrests of agents and attempts to get them out of prison, numbers of Allied airmen and Dutch fugitives passing through Paris and the like. They also consistently describe our man’s train journeys. I can tell you if the train between Lyon and Paris on a particular day in December 1943 was heated (it wasn’t) or why the train between Toulouse and Paris was delayed on a particular day in January 1944 (two sabotage attacks on the rails, one of which derailed the first carriages of the train, causing several injuries). I can also tell you how many times our man’s papers were checked, where, and by whom (Germans, Frenchmen or Belgians).

I had at first thought that the comments about conditions on the trains were the reflexes of a tired traveler explaining why it took him so long to get anywhere. But I’ve since come to think that they were in the reports at the request of the Dutch military attaché in Bern. After all, the General had regular contacts with his British and American counterparts about getting downed Allied airmen out of Occupied Europe.

So it stands to reason that he was also gathering information for them about the effects of the Allied bombing campaign. Our man doesn’t just mention delays and damage, he also records the attitude of the local population about being bombed. If the people of Annecy are angry at the Americans for bombing their town without any obvious military reason, he mentions it. If the Belgians take being bombed as a matter of course, he mentions that.

And if he just happens to talk to a German officer on a train bound to Paris on 30 March 1944, he mentions both the officer’s regiment and that the German thought that if one continued to bomb Germany as it was being bombed, it wouldn’t be able to hold on past May [1944].

You have to admire the sang-froid of a businessman who is carrying three illegal microfilms through occupied territory and spends the extra nine hours that his train is delayed by sabotage attacks to mingle with enemy officers.

In fact, you have to admire the stamina, if not the courage, of anybody who got on a train in Belgium or France between October 1943 and June 1944 because the trains were usually late. More often than not, they were late because the rails or the trains themselves were attacked from the air by the Allies or the ground by the Resistance. But that was such a little thing amongst the hunger, forced deportations and raging battles of the war that it gets overlooked.

- 0 Comments

- Tags: Belgium, Border Crossings, France, Switzerland

I’ve had many occasions over the last two weeks to remember what my friend at the Dutch Red Cross Archives pointed out: an archive preserves the idiosyncratic organization created by the person or institution that wrote the documents in it. An archive is not a library, where the books are arranged according to universally recognized categories. Furthermore, those original authors wrote the documents for their own ends, not the researcher’s.

That was all too apparent last week at the French military justice archives in Le Blanc (SHD, Le Blanc). Appropriately, these records are protected by several defensive rings. First one needs express, written permission to see any particular document held there. Then one needs to get there by car because they are kept far from public transport. In a military installation, behind a high wall topped with barbed wire. One surrenders one’s passport at the gate.

Once inside the bleakly bureaucratic building, however, the Colonel and his Adjoint could not be more gracious. But there was nothing they could do about the slender nature of the dossier I’d gone to such lengths to see. I was looking for the French interrogation reports of a German officer held in their custody after the war. But the German in question had not been tried by the French military tribunal on the technicality that he was paid by the Abwehr rather than the Gestapo. The court did not preserve any of the investigation into his activities because as far as the court was concerned, they weren’t necessary.

I had better luck at the Defense archives in Caen (SHD, Caen), which houses the papers of the Bureau of Former Victims of Contemporary Conflicts (BAVCC), which used to rule on whether an individual had the right to the title of “Deportee of the Resistance” or “Political Deportee” and such like, which had significant bearing on pensions, etc. The archive has a spiffy new reading room but hasn’t quite finished cataloging all the dossiers up in the attic. My thanks to Pascal Hureau for ferreting through the cabinets for so many relevant files for me.

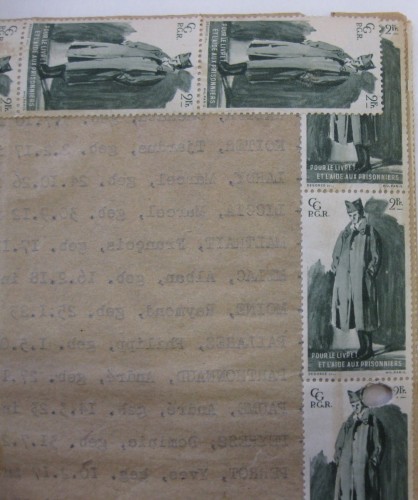

Of course, he could only find something if the resister in question or his or her family had caused the original administration to open a file on that person. It would be hard to forget that most of these papers were written by civil servants of the Ministry of Prisoners of War, Deportees and Refugees because many of them had POW stamps lining or framing the back.

Vichy POW stamps

I asked Monsieur Hureau about this unusual embellishment to government documents. He explained that during the war the Vichy Ministry of Prisoners of War and Refugees (PGR in French) had sold these stamps to raise money for the more than one million French POWs captive in Germany. After the war, when they’d become de Gaulle’s Ministry for Prisoners of War, Deportees and Refugees (PGDR in French), they still had an important stock of stamps, but no scotch tape. So they used the stamps to reinforce the wartime paper.

It’s a good reminder of the material roots of all history, and of the archives from which it’s pieced back together.

- 0 Comments

- Tags: France

Message in a Flashlight

The situation in Occupied Europe was so fluid and communications so tenuous, that sometimes even the professional spooks didn’t believe what was going on.

Take the story of a young Dutchman we’ll call Kees. He was the son of a law professor at the University of Leiden, a member of the Leiden hockey team and an economics student in Rotterdam, all of which means that he was well-educated and well-connected. He left the Netherlands without the help of any organized group on 1 December 1943 and arrived in England on 16 March 1944, which was about as quick as you could get to Spain and then back out of the hands of the Spanish, who preferred to stash men of military age in a truly miserable internment camp.

Once he got to England, the British put Kees and all other Allied nationals in the Royal Patriotic School, where they were interrogated before being allowed the freedom of the country. The British were looking for German spies. They were particularly interested in Kees because he’d been telling a cockamamie story Read the rest of this entry »

The Balance between Ice Cream and Barbed Wire

In October 1943 John Weidner went on a secret mission for the Dutch military attaché in Switzerland. He left Geneva at 1:00 pm on a Wednesday and crossed the border with the help of an unidentified “R”. On the French side of the border he took the bus from St-Julien to Annecy, arriving at 3pm. Two hours later, he took the train to Paris, arriving at 7:00 am on Thursday without more than a documents check by Germans. He departed from Paris at 8:00 am to arrive in Brussels at 3:00 pm, again without serious difficulties. By 4:00 pm he had made contact with the person he was meeting, a certain “N”.

Weidner’s mission was to give “N” some documents in exchange for others. But “N”’s man hadn’t come from Holland with the documents yet, so Weidner spent the weekend in Brussels as the guest of “N”. They discussed their common interests in helping refugees and moving information, and “N” introduced Weidner to some of his contacts in Brussels.

Even though the papers hadn’t shown up by Monday morning, Weidner left Brussels as per his instructions. Without more than the usual customs and documents formalities, he arrived in Paris at 3:00 pm on Monday. He made contact with several members of the Dutch colony there, again discussing the possibility of coordinating efforts to help Dutch refugees, and caught the train at 10 pm. He arrived in Annecy at 10:00 am on Tuesday with nothing more than a German document verification in Dijon to trouble him. He took the bus back to Saint-Julien, arriving an hour later. And at 12:30 pm on Tuesday, Weidner crossed the Swiss border. He reported that it didn’t seem to be absolutely guarded by the Germans, but it had been raining hard that day.

Weidner ended his report with the plans he’d made to get the missing documents to Geneva and the following summary:

“Even though, in my opinion, the results of my mission did not equal the great risks of my voyage, I nonetheless had the satisfaction of eating some excellent French fries in Belgium and some of that famous ice cream. On the other hand, I got two rips in my pants while crossing through the Swiss barbed wire….. [sic] which has really pleased my wife.”

From which we can conclude that if a tendency to see the glass half full wasn’t an absolute necessity for bearing the risks of resistance, it certainly helped.

- 0 Comments

- Tags: Belgium, Border Crossings, Switzerland

The war impelled all sorts of people to extraordinary acts, not least of them mothers. Take, for instance, the wife of the Dutch consul general in the Vichy zone of France. Madame, as we’ll call her, had four daughters but consistently refused opportunities to leave occupied Europe with them on the grounds that it was better for the whole family to stay together in times of trouble. Her husband the consul refused to leave on the grounds that, like the captain of a ship, he would not leave until the last Dutch refugee left.

So she kept them together and kept the girls on track in their education as the family moved from Bordeaux to Montauban to Vichy to Toulouse. After her husband was incarcerated in a spa hotel turned into a prison for high-ranking political prisoners such as generals and diplomats, she and the girls stayed in Toulouse. But the French Resistance paid her a visit to suggest that she move because a nearby ammunition factory was going to blow up. They went to a farm in the Dordogne. All was well until she received a message that her four children were going to be taken to Germany because her husband’s work helping Dutch refugees was continuing despite his imprisonment (thanks to John Weidner, among others).

Alarmed by this, she made a clandestine journey to Vichy by cover of night. There Madame, who was a devout Protestant, spoke to the Papal Nuncio, whom she had met before the war in Paris. The Nuncio invited Pierre Laval, the premier of the French State, better known as Vichy, to dinner the next night. And in the morning he told Madame that the rumor was true: her children were going to be taken to Germany.

The time had finally come to allow the girls to flee. Madame contacted her many friends in the Dutch resistance in France. A Seventh Day Adventist pastor in Lyon and his wife made false ID cards for the girls in their home and the pastor’s wife arrived at the farmhouse in Dordogne at 3am to escort the older two girls to Lyon. From there they took a Dutch-Paris route through Annecy to Switzerland, where the Dutch consul made arrangements for their lodging and education. When they had safely arrived, the younger two girls left by the same route. Walking through the snow to Switzerland in the cold January of 1944 was hardest on the youngest girl, who was only 12, but they made it.

Madame stayed in the town near her husband’s prison until the liberation of Paris caused his release and they both returned to Paris. When the consul general flew to London on the Dutch government-in-exile’s orders, his wife traveled to Switzerland to stay with the girls until they could all return to the Netherlands in 1945.

- 0 Comments

- Tags: Border Crossings, France, Switzerland, women

The Rescuers Rescued

Sixty-six years ago this week the Danish government and the Swedish Red Cross evacuated 7,000 female prisoners from the concentration camp at Ravensbrück, most likely saving their lives. The women traveled by the famous White Buses or train to ferries that took them to Sweden, where they were nursed back to sufficient health to return to their homes in the Netherlands, Belgium, France and Poland after the war ended in Europe in early May 1945.

The evacuation from Ravensbrück was part of an effort to evacuate Scandinavians from the prisons and camps of the Third Reich that began in March 1945. At first the Germans would only allow neutral Swedes to come in, but by the end most of the personnel and matériel were Danish. They took the Dutch, Belgian, French and Polish women to safety because, to their surprise, Read the rest of this entry »

- 0 Comments

- Tags: arrests, concentration camps