Searching for the Dutch-Paris Escape Line

Fighters Across Frontiers: Transnational Resistance in Europe 1936-1948

One of the unusual things about Dutch-Paris was that it involved many people from many different nations working together, across borders, in a common cause. In fact, Dutch-Paris routinely operated in three languages, using five different currencies with the odd American dollar or British pound sterling thrown in. It was, indeed, the quintessential transnational escape line because the resisters involved stopped thinking of Europe as a collection of different nations and nationalities and operated as if it were a continent divided solely by the circumstances of the war: pro-Nazi or not, occupied or not.

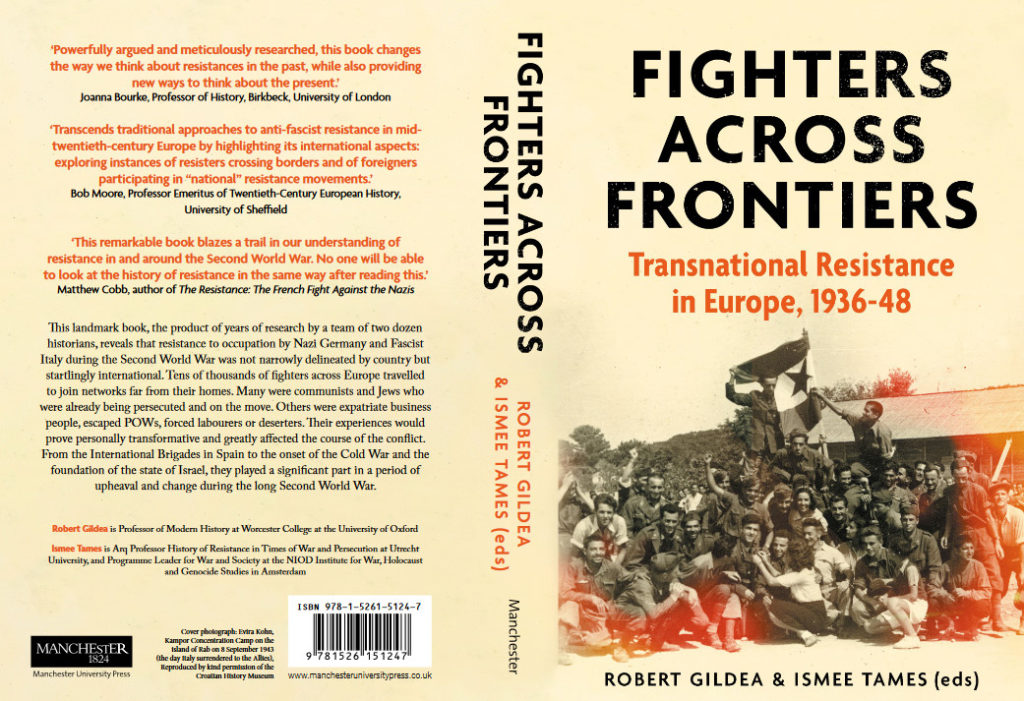

But the men and women of Dutch-Paris were not the only transnational resisters opposing the Nazis during the war. If you’re interested in a scholarly overview of transnational resistance, I highly recommend Fighters Across Frontiers, just published by the University of Manchester Press.

Full disclosure: I am one of the many authors of the book and have contributed to the chapter on escape lines (of course). I had the great privilege of being part of a three year research workshop on transnational resistance that included historians from all around Europe – Spain, France, the Netherlands, Italy, Great Britain, Switzerland, Greece, Serbia, the Czech Republic and Rumania – Israel, and myself as the one American. Our research has covered not only the continent but many different aspects of resistance, including partisans, foreigners in France, Jews, escape lines and others. And we’ve examined the “long war” 1936-1948, thereby including the Spanish Civil War and the turmoil after the German surrender.

This is all new material, in large part because it’s a new way of approaching the history of the Resistance. In the past, resistance was considered national in both motivation and location. That’s true for many resistance networks. But it leaves out the great displacement of people that occurred in the war as well as the uniting force of resistance to Nazism.

Leave a reply