Searching for the Dutch-Paris Escape Line

Single Issue Collabos

The most insidious collabos were those who threw in their lot with the Nazis – and the futures of their entire countries – for the sake of a single issue. Rather than looking at the whole picture and considering what the consequences of the entire Nazi package would be, they focused on one issue.

The most glaring example of this would be the Catholic bishops and priests who supported the Nazis because they were afraid of the Bolsheviks. The Bolsheviks, of course, took over the Russian empire during the Russian Revolution and created the Soviet Union as a communist state. And it has to be said that the Bolsheviks represented a clear and present danger, especially in German in the 1920s when Hitler was gaining followers. Lenin and the other Bolshevik leaders made no secret of their intention to take the communist revolution west. They announced several times that they would “be in Berlin” by the following year. Ironically, they didn’t make it to Berlin until the end of Hitler’s war in 1945, but no one knew that in 1942.

Many Europeans feared Read the rest of this entry »

- 0 Comments

- Tags: collaborators

Who was the Enemy of the Resistance?

If you were to think of the great moral heroes of the twentieth century, the Second World War Resistance would surely make the list. They did, after all, oppose the Nazis at great risk to themselves and their families. It’s worthwhile, however, to think about exactly who resisters fought against.

At first glance the simplest case appears to be the armed resisters such as the French maquis or FFI (French Forces of the Interior), who took up arms to liberate their country from Nazi occupiers. Sometimes that happened, but just as often, the partisans were fighting their own countrymen who had chosen collaboration with the Nazis, giving these shoot-outs the aspect of civil war.

To further complicate matters, many resisters never carried weapons. The men and women of Dutch-Paris, for instance, did their best not to engage the Nazis or their collaborators. They certainly never killed anyone. And yet the Gestapo considered them Read the rest of this entry »

- 0 Comments

- Tags: collaborators

In my last post I mentioned the legendary Comet Escape Line. It’s legendary because the men and women of Comet achieved the remarkable feat of rescuing hundreds of Allied servicemen from the Nazis. But it is also more literarily legendary as a story. It’s a legend in itself because it is the best known of the escape lines. But much of what is told about Comet is more legend than fact.

Comet has been a legend since the liberation of western Europe in 1944. In fact, when a Dutch-Paris resister, whom we’ll call Micheline, returned from the concentration camps in 1945 she wrote down on her official paperwork that she had belonged to Comet. When the authorities asked the leaders of Comet to verify this woman’s participation they said, quite rightly, that they could not. Micheline’s request for medical aid etc was denied. It took a considerable amount of paperwork and telephone calls on the part of the leaders of Dutch-Paris to get the clerical error fixed so that Micheline could get the help to which she was entitled.

Why did she say she was part of Comet? What probably happened was that she didn’t know the name of her resistance network because they always called themselves “the organization.” So she asked someone who said: “oh, you helped Allied aviators as part of an escape line that went through Paris? You must have been in Comet.” And she wrote down “Comet.”

Why did this unknown person assume that Micheline must have been in Comet? It was undoubtedly the best known of the escape lines, possibly the only one known at the time. That was because Comet was the work of and always under the leadership and control of Belgian civilians, but it was funded by the British and most of the people they helped were Allied servicemen. In fact, Comet began as a way to get British soldiers who had been left behind at Dunkirk and taken shelter with Belgian families back to England. After the first soldiers whom they took to Spain were arrested by Franco’s police, the leaders of Comet made a point of passing their charges directly to British officials in Spain.

So Comet was known in the outside world from its beginning in 1941. It also had a certain glamour as Read the rest of this entry »

One of the Comet escape line’s teenage couriers recently passed away at the age of 95. Like Dutch-Paris, Comet was also created by civilians. Unlike Dutch-Paris, Comet emphasized helping Allied servicemen to evade the Nazis by either taking them from Belgium to Spain or hiding them in Belgium.

Both escape lines relied on the dedication and courage of men and women of all ages. And they both used teenagers as couriers and guides. By teenagers I mean boys and girls who were still living at home and going to high school, not young men and women who had already launched on university or business careers.

In every case that I know of, the teenagers started working for the escape line because one of their relatives, usually a parent, was heavily involved in the escape line. At some point, the adult relative needed someone to carry a message or fetch a fugitive. And so a 14 year old boy walked nine miles in the dark to bring aviators from the place where they were hiding to Read the rest of this entry »

A couple of posts ago, we were talking about how Dutch-Paris took care of the medical needs of their fugitives in Brussels and Paris. The situation was different again in the Pyrenees. The problem with guiding men over the Pyrenees in winter in the dark was that it was a hazardous trip even without the Germans lurking around every boulder.

Most of the Engelandvaarders and aviators escaping to Spain by walking over the Pyrenees, for example, were not wearing adequate boots. For two reasons, most of them had rather flimsy city shoes that didn’t fit properly. First, wearing hiking boots on the train from Paris to Toulouse would have looked very suspicious to Read the rest of this entry »

- 0 Comments

- Tags: Allied airmen, Border Crossings, France, Pyrenees, women

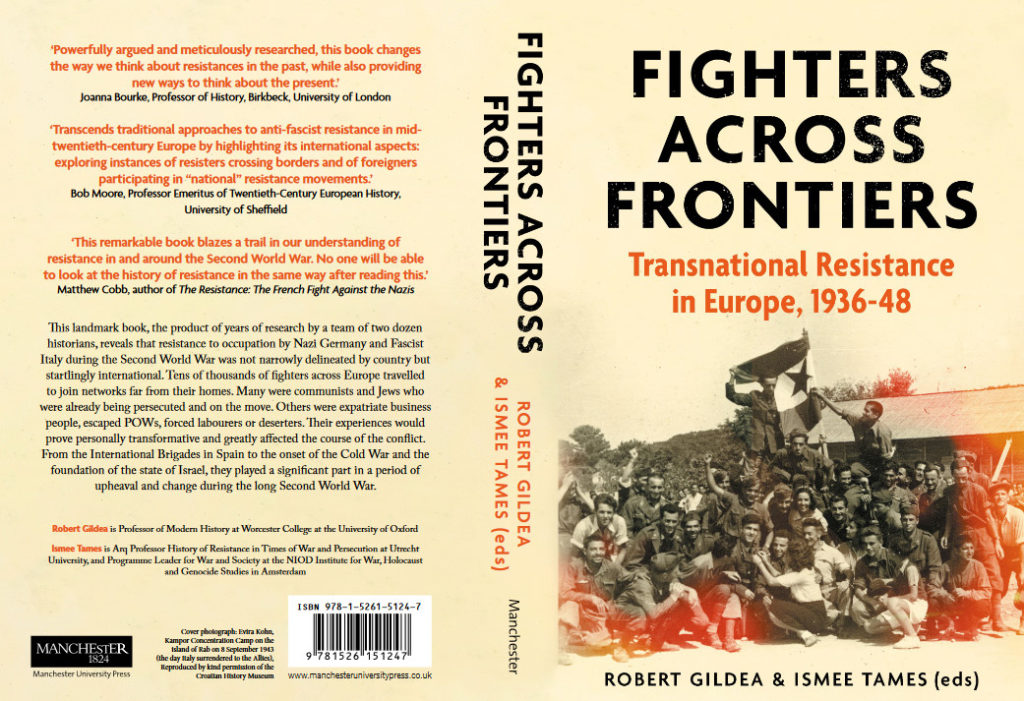

Fighters Across Frontiers: Transnational Resistance in Europe 1936-1948

One of the unusual things about Dutch-Paris was that it involved many people from many different nations working together, across borders, in a common cause. In fact, Dutch-Paris routinely operated in three languages, using five different currencies with the odd American dollar or British pound sterling thrown in. It was, indeed, the quintessential transnational escape line because the resisters involved stopped thinking of Europe as a collection of different nations and nationalities and operated as if it were a continent divided solely by the circumstances of the war: pro-Nazi or not, occupied or not.

But the men and women of Dutch-Paris were not the only Read the rest of this entry »

The Grim Cost of Nursing an Evading Airman

In my last post I mentioned a Dutch-Paris resister in Paris whom we’ll call Micheline. She acted as a nurse to aviators who needed medical help in Paris. One of these was an Englishman whose childhood polio recurred while he was on the run from the Germans.

When the Germans rolled up the Dutch-Paris aviator line in Paris in February 1944, this Englishman was in the apartment next door to Micheline’s. It belonged to a Swiss man who was also part of the network. The German police appear to have known that both of them were involved in Dutch-Paris before they arrived at their apartment building. Both were arrested, along with the RAF pilot.

Soon after the arrests, other Germans in big trucks arrived to strip the two apartments of Read the rest of this entry »

- 0 Comments

- Tags: Allied airmen, arrests, France, women

Medical Care for Evading Airmen

Dutch-Paris’s clandestine medical needs were different in Paris than in Brussels. The Comité in Brussels was directly sheltering and supporting hundreds of Jews hiding in the city. In Paris, Dutch-Paris hid fugitives of various sorts temporarily while they moved through northern France on their way to Spain or Switzerland. Which is not to say that they didn’t sometimes need medical care.

For example, an American aviator developed a skin condition while he was in Paris. It was bad enough that his helpers did not think he could continue on his journey until it had healed. So they had to find a place for him to stay after his companions left on a night train for Toulouse. They also had to find a doctor and Read the rest of this entry »

- 0 Comments

- Tags: Allied airmen, France, women

What did rescuers do if a fugitive they were sheltering needed medical attention? After all, people were in hiding for years. Someone had to have developed an abscessed tooth or appendicitis.

The rescuers in Dutch-Paris, who helped thousands of fugitives, developed relationships with doctors and nurses for exactly such eventualities. In Brussels, the Comité was caring for over 400 Jews hiding in and around the city at the time of the Liberation in September 1944. Not surprisingly, they had the most formally organized system of clandestine medical care in the entire Dutch-Paris network.

The wife of one of the leaders of the Comité in Brussels had been the director of the Protestant clinic in Brussels until her marriage in 1939. During the war, the clinic treated Germans. But it also treated a Canadian aviator and Jews. Obviously, the protocols were a little different for a German than for a Canadian.

Doctors would sometimes perform clandestine operations after hours. Or a hospital might Read the rest of this entry »

- 0 Comments

- Tags: Belgium, Jews, women

The Cinemas were Open during the Occupation

An old friend of mine said something profound this summer. The lock down had been lifted here in Michigan, so it was possible to move about, although many public gathering spaces were still closed, including theaters, gyms, bowling alleys and banquet halls. Restaurants and cafes were allowed to be open with tables spread far apart, preferably outside. Everyone was required to wear a mask inside any public place as well as outside if the place was crowded.

My friend and I were sitting outside talking, a good 50 yards from the nearest other human being. She said: “I know this isn’t as bad as a war. But at least during a war you could go to a show or have dinner with friends.” Meaning that during a war you didn’t have to Read the rest of this entry »

- 0 Comments

- Tags: Allied airmen