Searching for the Dutch-Paris Escape Line

Bomber Buffing

Some weeks ago I joined other volunteers at the Yankee Air Museum in Belleville, Michigan, for their annual bomber buffing. That’s when we all get clean cloths and little pots of aluminum polish to shine up the museum’s B-17 bomber before it makes its annual rounds of air shows.

It was thrilling to stand on the wing of a B-17 and think about the missions that that plane and thousands like it flew during WWII to defeat the Third Reich. But it was also sobering to think about the young men of a B-17 or any bomber’s crew. By today’s standards, that plane is flimsy and small. Conditions were uncomfortable and dangerous, and a good many of the crews never returned because of malfunctions or enemy fire. A few men who bailed out of or crash landed in B-17s ended up in the hands of Dutch-Paris in early 1944. Dutch-Paris took them through safe houses in Brussels, Paris and Toulouse and then by foot over the Pyrenees to Spain. Once in Spain the British and American authorities got them back to their bases in England.

It was even more sobering to think of the men, women and children who were on the ground where those bombers dropped their bombs. No one who has sat through an air raid in an air raid shelter has ever forgotten the fear and disruption. Of course many didn’t survive to remember, including at least one Dutch-Paris resister who died when his concentration camp was bombed. It goes without saying that the prisoners were not the target, but bombing was not a precision science. That’s part of what made the Second World War such an overwhelming catastrophe.

Still, if not for the B-17 and other planes and their crews, would the Allies have won the war? Would we all be speaking German and saluting with our arms outstretched now?

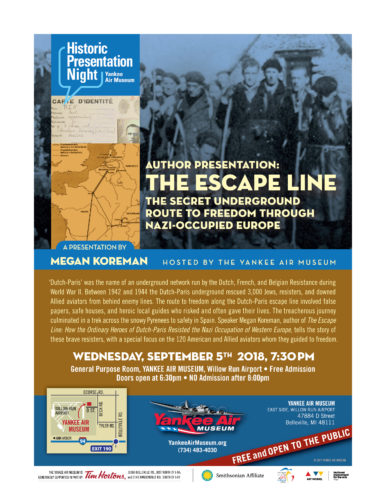

I’ll be giving a talk about Dutch-Paris and its help to Allied aviators at the Yankee Air Museum on September 5, 2018. Here’s the flyer:

- Tags: Allied airmen

Leave a reply