Searching for the Dutch-Paris Escape Line

A New Station Chief in Paris

Seventy-five years and a couple of weeks ago, in November 1943, Jean Weidner travelled to occupied Paris to find resisters who would be willing to join the new escape line that we know as Dutch-Paris. It wasn’t the kind of thing you could advertise in the newspapers, and Weidner hadn’t been in the city since the Wehrmacht marched in in June 1940. But he had heard about a minor diplomat at the Dutch embassy who had been involved in resistance pretty much since the first day the Germans had shown up. We’ll call him Felix.

Felix hasn’t survived underground as long as he had without being careful. He agreed to meet Weidner for the first time on a crowded street that had plenty of exits if Weidner’s sister made the introduction. And he didn’t trust Weidner’s claim that he had the Read the rest of this entry »

Arrest in Brussels, 1943

Seventy-five years ago today, on November 18, 1943, the young man in charge of daily operations for the Comité in Brussels was arrested. This was not the first time that this particular young Dutchman, we’ll call him Paul, had been arrested. He and his entire family had been captured as they fled from their home in the Netherlands towards Switzerland. Paul had jumped out of the train taking them all to Auschwitz. He’d made his way to the home of a friend of his father’s in Brussels. They introduced him to the Comité.

Paul was in charge of the Comité’s daily operations of making sure that fugitives had hiding places and got regular deliveries of money and false documents. He also had to figure out how to get some of the people they were helping to Switzerland or Spain. The Comité had already agreed to join in Jean Weidner’s new escape line at that point, but the new route wasn’t quite functioning yet. So Paul went to the apartment of an elderly widow to meet with the members of a separate escape line who had a way to get aviators out of occupied Europe.

Unfortunately, Paul wasn’t the only one who knew about this other escape line. The Germans Read the rest of this entry »

Jean Weidner’s Papers Now Open at the Hoover Archives

When Jean Weidner left Switzerland to link up with like-minded resisters in Brussels on October 13, 1943 (see the last post), he left Switzerland with the unofficial blessing of the Dutch embassy in Switzerland and the Swiss intelligence services. The immediate and most important implication of this unofficial sanction was that Weidner had enough money to continue the rescue work of his colleagues in southern France and to expand it throughout France and Belgium. Dutch-Paris was created and hundreds of people’s lives were saved.

On a far less dramatic level, the unofficial support meant that Weidner had to write reports about his bi-weekly trips through occupied France and Belgium on Dutch-Paris business. He typed these in Switzerland using codes for names and places. The report went to the very secure Dutch embassy, and Weidner kept a carbon copy for himself. At the time, this undoubtedly seemed like a petty bureaucratic chore which might put a number of people in danger if it fell into enemy hands. That is undoubtedly why Weidner never gets any more specific with addresses than the code name of a city and is pretty sparing with personal names.

Today, though, these reports are a unique treasure trove for the historian. Resisters did not usually write down their movements. Weidner certainly didn’t do anything of the kind before he started using government funds for their rescue work. But having written them, he kept his carbon copies and a lot of other documents. At the end of his long life he donated his papers to the John Henry Weidner Foundation for the Cultivation of the Altruistic Spirit, now called the Weidner Foundation for Altruism (weidnerfoundation.org). The Weidner Foundation hired an archivist and put Weidner’s papers into archival order. They allowed me to read them while I was researching The Escape Line, and a few years ago they donated them to the Hoover Library & Archives at Stanford University.

The Hoover Library & Archives have an amazing collection of documents relating to war and peace in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. They have documents about the Second World War and Resistance in Europe that you won’t find anywhere else. I’m happy to announce that the Weidner Papers are now open for researchers. You can consult the (partial) finding aid at https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8kd2194/entire_text/ . The Weidner Papers will not be digitized; this link is only for the catalog. If you’re interested in a particular person, you can also consult the footnotes of The Escape Line to find the relevant catalog number.

Unfortunately, the Hoover Archives will be closed to the public from December 24, 2018 until early 2020 because of a massive construction project. If there’s something you need to see in the Weidner Papers before 2020, you should contact them right away (hooverarchives@stanford.edu). If you’re reading this during the construction project, look in the back of The Escape Line for a list of over two dozen other archives with documents relating to Dutch-Paris.

75th Anniversary of the Creation of Dutch-Paris

Just about 75 years ago, on October 13, 1943, Jean Weidner left Switzerland illegally but with the assistance of a Swiss officer, to create the Dutch-Paris escape line. Up until this point, he and his colleagues had been running an escape line between Lyon (France) and Geneva (Switzerland). Weidner himself had not been to northern France, let alone Belgium or the Netherlands, since the war started.

But in September 1943 Weidner had a meeting with the Dutch ambassador to Switzerland and the president of the World Council of Churches in Formation (another Dutchman). The ambassador and the pastor had a proposal for Weidner. The Dutch government in exile would fund Weidner’s rescue efforts in France and later in Belgium and give him and his colleagues complete autonomy to act as they thought best in occupied territory if they did two things. (1) They expanded their escape line north to the Netherlands and south to Spain in order to bring particular individuals from occupied Holland to Spain so those individuals could join the Dutch government in exile in London. (2) They established a courier route to shuttle microfilms between Amsterdam and Geneva as a way for the Dutch resistance to communicate with Queen Wilhelmina and her exiled government. Weidner accepted the proposition on behalf of his small resistance network on the Swiss border.

On October 13, 1944, Weidner was heading toward Brussels where he already had connections with a group of resisters who are known as the Committee for the Support of Dutch War Victims in Belgium. They were hiding Jews in and around Brussels and looking for ways to get Jews to Switzerland and young Dutch volunteers to Spain. They were also running out of money. It didn’t take much convincing on Weidner’s part to get the Committee to join his expanding network. After all, they’d been doing the same kind of rescue work since 1942. And Weidner offered both money and a secure route to Switzerland and Spain. It did take a few weeks of parlaying with the ambassador about the money, though, because illegal negotiations like that had to be hand delivered by couriers who were risking their lives and traveling across several borders at a time of decidedly slow travel.

It was harder to link up with like-minded resisters in Paris, but that’s a story for next month.

The End of Italian Occupation

A little more than 75 years ago, on 8 September 1943 Italy surrendered to the Allies. The next day, on 9 September 1943, German troops occupied the Alpine departments of France bordering Switzerland and Italy that had been the Italian occupation zone since early November 1942. This counted as a catastrophe for unknown thousands of people who had fled into the Italian zone as a refuge from both German and French persecution. While they were in charge, the Italian occupation authorities simply refused to turn anyone over to anyone else. Dutch-Paris had settled a number of Jewish refugees in French villages in Haute-Savoie and Savoie because they believed that the Italians would not harm them. They weren’t so foolish as to think that Italian border guards would not shoot at resisters, but that was a different matter.

In early September 1943, however, the Italians were no longer in a position to protect anyone from anyone else. They could not even Read the rest of this entry »

- 0 Comments

- Tags: France, Switzerland

A history book about an event in living memory is never finished. Sure, the historian can spend years reading thousands of documents in over 30 archives, but there will still be details that aren’t in the documents. This is especially true in the case of Dutch-Paris because it was a clandestine network spread over half a continent and some of the people involved died before they could file a report on their activities. The book itself will bring new details to light, although they may turn out to be not entirely accurate.

Here’s an example. A couple of weeks ago I received a message from an Engelandvaarder friend in Tasmania who journeyed from Paris to Spain via Dutch-Paris when he was a young man in 1944. Rudy regretted to inform me that I had made an error on a particular page of The Escape Line regarding the escape of the Dutch statesman GJ van Heuven Goedhart. Rudy wanted to know where I had gotten my information because he has a very clear memory of talking to Van Heuven Goedhart’s three Engelandvaarder companions at a hotel in Llerida, Spain, on a date that I claim the man was still in France.

I have the utmost respect for Rudy’s memory in these matters and have benefited tremendously from his unpublished memoirs and his help. But the information in the book comes from Van Heuven Goedhart’s own book, his sworn testimony before a Dutch parliamentary committee, and a whole lot of reports written about it at the time. The Dutch government in exile was very anxious about his safe escape from occupied Europe.

Rudy himself immediately understood what had happened. He Read the rest of this entry »

Failed Intimidation

Seventy-five years ago this week, on 6 September 1943, German occupation authorities in Lyon arrested the Dutch consul there. They also arrested the French bureaucrat who was his official supervisor in the matter of administering foreign nationals in southern France. The Gestapo accused the Consul of helping Dutch refugees, particularly Jewish refugees, in illegal ways, such as providing false documentation claiming that they were Christians. The charges may or may not have been accurate in the details but they were certainly true enough. The consul was heavily involved in hiding fugitives from the Germans and had passed a number of Jews to Weidner to be taken to Switzerland.

The fact that the Gestapo had arrested a foreign Consul caused rather a stir in Lyon and the Spanish consul intervened on the two men’s behalf. The Spanish consul had a little more weight than others because he represented Franco’s regime. Spain was officially neutral, but Hitler had helped put Franco in power. Perhaps because of the public notice, the Dutch consul, who was actually a Frenchman who did not speak any Dutch, and the French bureaucrat nominally responsible for him, were not mistreated while in German custody. They were questioned but not Read the rest of this entry »

- 0 Comments

- Tags: arrests, France

Dutch-Paris Events

There’s a new feature on the blog called “Upcoming Events.” It’s on the top of the right hand column inside a WWII-era identity card issued by the city of Brussels (Ville de Bruxelles). You can see what’s coming up at a glance and get more details by clicking on “view all events” at the bottom of that box. If you’re in the neighborhood of any Dutch-Paris events, please stop by. If there’s a place in your town that you think would like to host a talk about Dutch-Paris, please share your idea.

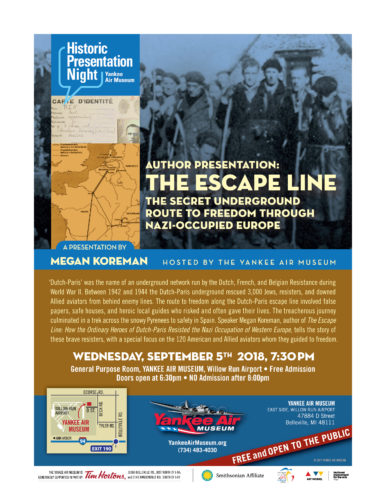

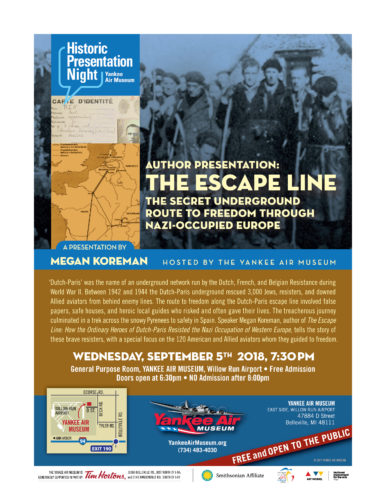

I’ll be giving a couple of lectures in September in the metro Detroit area. Both are free and open to the public. On September 5th I’ll give a presentation about Dutch-Paris’s aviator escape line at the Yankee Air Museum at the old Willow Run airport where so many bombers were built. It’s an interesting museum featuring the planes flown by the USAAF and the USAF and, of course, the Rosie the Riveters who built the planes flown by the aviators helped by Dutch-Paris. Here’s their website http://yankeeairmuseum.org/events/ And here’s the flyer for my talk.

A week later, on September 13, I’ll give a presentation about Dutch-Paris as a whole at the Royal Oak Public Library in Royal Oak, MI. Here’s the link http://www.ropl.org There’s a lot of construction going on in downtown Royal Oak, so you’ll want to park in the Farmers’ Market lot just west of the library to avoid having to walk around it.

In October I’ll be in California, speaking at the Hoover Archives and Library on October 2. The Hoover now houses Jean Weidner’s private papers, so this is a celebration of both The Escape Line and the Hoover’s surprisingly extensive and unique collection of documents on the Resistance during WWII.

On October 3 I’ll be giving a lecture at the San Francisco Jewish Community Library. Here’s the link for that: http://www.jewishlearningworks.org They have a parking garage around the corner. This is also free and open to the public.

An Official Border Crossing in 1943

Seventy-five years ago yesterday, on 11 August 1943, Jean Weidner crossed the border from France to Switzerland and announced himself to a Swiss border guard. He filled out the usual form for people who crossed the border without going through an official crossing point and surrendered the cash in his pocket. Then he went off to the quarantine camp outside of Geneva like all the rest of the day’s refugees. None of this sounds at all out of the ordinary – except perhaps that he was carrying American dollars and British pounds sterling in occupied Europe – until you remember that Weidner went in and out of Switzerland on a regular basis on business or to visit his mother-in-law without ever alerting the Swiss authorities to his presence.

So why go through the official procedures this time? This time Weidner was there at the request of the Dutch embassy in Bern. The ambassador was keen to stay on the good side of the Swiss, who had, after all, allowed a number of Dutch refugees into their country. At this time Weidner was unofficially representing the Dutch government in exile in Vichy when it came to matters regarding the welfare and support of Dutch citizens in Vichy France. By unofficial, I mean unofficial in Switzerland and illegal and Read the rest of this entry »

Bomber Buffing

Some weeks ago I joined other volunteers at the Yankee Air Museum in Belleville, Michigan, for their annual bomber buffing. That’s when we all get clean cloths and little pots of aluminum polish to shine up the museum’s B-17 bomber before it makes its annual rounds of air shows.

It was thrilling to stand on the wing of a B-17 and think about the missions that that plane and thousands like it flew during WWII to defeat the Third Reich. But it was also sobering to think about the young men of a B-17 or any bomber’s crew. By today’s standards, that plane is flimsy and small. Conditions were uncomfortable and dangerous, and a good many of the crews never returned because of malfunctions or enemy fire. A few men who bailed out of or crash landed in B-17s ended up in the hands of Dutch-Paris in early 1944. Dutch-Paris took them through safe houses in Brussels, Paris and Toulouse and then by foot over the Pyrenees to Spain. Once in Spain the British and American authorities got them back to their bases in England.

It was even more sobering to think of the men, women and children who were on the ground where those bombers dropped their bombs. No one who has sat through an air raid in an air raid shelter has ever forgotten the fear and disruption. Of course many didn’t survive to remember, including at least one Dutch-Paris resister who died when his concentration camp was bombed. It goes without saying that the prisoners were not the target, but bombing was not a precision science. That’s part of what made the Second World War such an overwhelming catastrophe.

Still, if not for the B-17 and other planes and their crews, would the Allies have won the war? Would we all be speaking German and saluting with our arms outstretched now?

I’ll be giving a talk about Dutch-Paris and its help to Allied aviators at the Yankee Air Museum on September 5, 2018. Here’s the flyer:

- 0 Comments

- Tags: Allied airmen