Searching for the Dutch-Paris Escape Line

How do you Send Mail to Someone Living Underground?

Here’s an interesting question that came up during the proof reading for the Dutch translation of the book.

Before the days of commercial air travel and cheap long distance phone calls, let alone the internet, travel took time and involved a lot more surprises than it does today. You might set out for a foreign city without knowing where you would stay or exactly when you would be there. But how could the people back home contact you if you did not have an address? The post offices had a device for this situation called “poste restante.” The person back home addressed the envelope to a name, a city and “poste restante”. The traveler went to that particular post office in the city and asked if there was any mail for him or her. It worked quite well if no one was in a hurry.

Paris being the gigantic city that it is, you could address “poste restante” mail to train stations as well as post offices. This was, of course, very convenient because even if you were just passing through Paris, you could pick up your mail.

During the war, one of Dutch-Paris’s leaders told his comrades that they could send him messages addressed to “Mr van den Hove uit [from] Bending” poste restante at the Gare St Lazare. Mr van den Hove was obviously a false name. But the copy editor wanted to know about the town of Bending. Where was it? Was it spelled correctly? Because there is no Read the rest of this entry »

- 0 Comments

- Tags: aliases, France

I am happy to report that the Dutch translation of my book on Dutch-Paris has arrived from the printers. Many thanks to Maarten Eliasar, Hélène Lesger and the rest of the production team for the terrific job they did with the translation, the copy editing, the illustrations and all the details that have made it such a fine looking book. It will be at Dutch bookshops starting this weekend. (Gewone Helden: de Dutch-Paris ontsnappingslijn 1942-1945, ISBN 978 90 5875 5568).

Also this weekend, the Dutch tv programme Andere Tijden will broadcast an episode called Ontsnappingsroute in de oorlog (Escape Route during the War). It will air at 21.10 on Saturday 5 November on NPO2. You can follow this link for the preview (in Dutch and some French) http://www.anderetijden.nl/programma/1/Andere-Tijden/aflevering/682/Ontsnappingsroute-in-de-oorlog The link includes a sublink to the 1967 Dutch documentary about Dutch-Paris, which has footage of many of the line’s leaders.

I have not been involved in making the documentary, but every researcher’s favorite archivist, Sierk Plantinga has been interviewed extensively for it. Some of you may have already seen him talking about a postcard sent from the Third Reich on the tv preview for the show. I don’t know if the entire show is about Dutch-Paris, but at least part of it is. I can’t wait to see it.

The Train Stations Used by Dutch-Paris

If you read the earlier post about trains, you know that a lot has changed about railway journeys since 1944. Another thing that has changed in some places, is the train stations. On a small scale, you used to have to buy a “platform ticket” in order to enter the platforms. So if you wanted to walk your sweetheart to the door of the train to bid him or her a tearful adieu, you needed to buy yourself a ticket to get that close to the train. This could have unexpected consequences. In December 1943 a Dutch-Paris guide could not get platform tickets for the early train out of Toulouse. When she came back for the afternoon train, the Gestapo arrested her on the platform.

On a larger scale, some of the train stations have changed beyond recognition. The station in the small mountain town of Annecy, for example, has been completely rebuilt in the last five years. It is now an ultramodern structure of glass and steel. During the war it looked like this:

If you took a train from Paris to Lyon Read the rest of this entry »

Wartime Railway Journeys

If you were to trace the steps of Dutch-Paris couriers and guides, you would do most of it by train. Like all civilians during the occupation, they relied on the railway to get themselves and those they were helping from one city to another. So you could get on a train in Amsterdam and follow the same route as an Engelandvaarder to Toulouse.

But you could not entirely re-create the journey. Obviously, Europe is not at war and who would really want to experience the anxiety of Gestapo identity checks and possible air raids? But there are more peaceable differences between then and now as well.

The European Union has abolished the international border crossings, so you no longer have to get off the train, shuffle through customs and passport control, and get back on the train when leaving one country and entering another.

There are also fewer trains now than there were in 1944. Belgium had an impressively dense network of trains and tram, many of which have been replaced by roads for automobiles. Likewise, many of the current roads in the Pyrenees were train tracks in 1944.

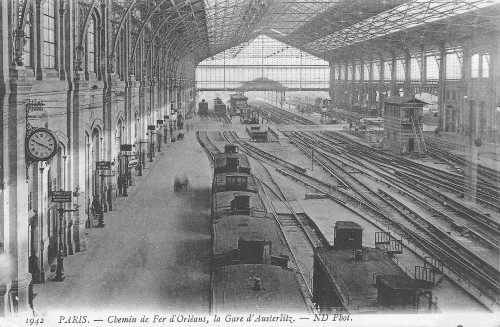

The trains themselves were different as well, as you can see in this postcard of the Gare d’Austerlitz in Paris.  Many of them had first, second and third class carriages. Only the most modern of them had the connecting carriages that we take for granted today. The upside of the old-fashioned trains in which you had to get off the train altogether and walk along the platform to get into the next carriage, was that the German police didn’t much care for them. At least in the Pyrenees, they preferred the modern trains with carriages that they could walk between while the train was in motion and rarely controlled passports in the old fashioned trains.

Many of them had first, second and third class carriages. Only the most modern of them had the connecting carriages that we take for granted today. The upside of the old-fashioned trains in which you had to get off the train altogether and walk along the platform to get into the next carriage, was that the German police didn’t much care for them. At least in the Pyrenees, they preferred the modern trains with carriages that they could walk between while the train was in motion and rarely controlled passports in the old fashioned trains.

Wartime trains were also big polluters, billowing out huge clouds of steam laden with coal dust. Today you need to visit a railway museum to smell that particular combination of hot, damp coal and metal. The steam of the trains created its own atmosphere in the train stations as well as causing continual negotiations among passengers about opening or shutting the windows. Closing them kept out the soot. Opening them allowed for the possibility of some air as well as lessening the impact of any possible explosions. None of the trains, even the most modern, had air conditioning.

In fact, compared to today’s high speed, international train travel, even the most uneventful first class train journey during the occupation was slow, inconvenient and uncomfortable. But it was the best available and the men and women of Dutch-Paris relied on it.

- 0 Comments

- Tags: Border Crossings

Dutch-Paris, the Book and the Symposium

I am pleased to announce that Boom uitgevers Amsterdam will publish the Dutch translation of my book this November. Gewone Helden: de Dutch-Paris ontsnappingslijn 1942-1945 (ISBN 978 90 5875 5568) will be available at book sellers or as an e-book starting on 5 November 2016. Oxford University Press will publish the English edition in early 2018. And, yes, I do use everyone’s real name in the book and there are photographs of some of the resisters and the people they helped.

Oxford University Press will publish the English edition in early 2018. And, yes, I do use everyone’s real name in the book and there are photographs of some of the resisters and the people they helped.

To celebrate the release of the book, we invite you to a mini-symposium on Dutch-Paris to be held at the Amsterdam Hilton on the afternoon of Thursday, 10 November 2016. I will tell the short version of the story of Dutch-Paris. Then we will have a lively discussion with a panel of experts and the audience. The experts include Hans Blom, historian and former director of NIOD; Ad van Liempt, author, journalist and tv producer; Onno Sinke, historian and advisor at Arq Psychotrauma Expert Groep, and Max van Weezel, political scientist, journalist and radio anchor. The symposium will be held in English.

The mini-symposium is, of course, free of charge. But we ask anyone who intends to join us to please register so that we have enough chairs and coffee cups for everyone. You can register very easily by clicking on the blue “symposium” tab above or clicking on this link. They both take you to the same place. Please register as soon as possible, but certainly before 20 October.

If you have a family connection to Dutch-Paris because, for example, your mother or grandfather worked in the line or was helped by it, please let us know by sending a message to the symposium’s host, Maarten Eliasar, at amsterdam@dutchparis.com.

For those of you who enjoy quality documentaries, the Dutch tv program ‘Andere Tijden ’ will feature Dutch-Paris in the episode “Ontsnappingsroute in de oorlog” at about 21.10 hours on 5 November 2016 on Dutch public network NPO2. No one is more curious to see this than I am, because although it is based on my book, I’ve had very little to do with it. I do know that they have interviewed individuals who were involved with the line in one way or another.

That will be an exciting week for me and everyone who has been involved in the book. We hope to see you at the mini-symposium on 10 November.

The Fugitive Needed a Doctor

Rescuing people during the Second World War the way Dutch-Paris did was one of those projects that just keep getting more complicated the further you get into it. It sounds straight forward enough: take a person from point A to point B. Of course there are obvious problems such as money, false documents and transportation. But there are also a whole host of secondary problems lurking in the details. Medical care, for example.

During the occupation, many civilians suffered from chronic medical problems because of the shortages of food and heating fuel and, for some, the bone-weary fatigue that comes from spending nights in air raid shelters. In addition to the general hunger and cold, some of the people whom Dutch-Paris helped also had to hide in confined spaces without fresh air or exercise for long periods. In addition, few of the aviators whom they rescued had been injured when their airplanes crashed or they had bailed out.

The shortages that sapped civilians’ health also compromised the public health services, starting with the number of doctors available. In France some doctors spent the war as POWs. In the Netherlands some doctors lost their licenses by refusing to cooperate with the Nazis. And everywhere Jewish physicians were forbidden to practice. Those doctors and nurses still at their posts did not Read the rest of this entry »

- 0 Comments

- Tags: Allied airmen, Belgium, France, The Netherlands

Why Was the Document Written?

The most important question to ask about any document is why the person who wrote it took the trouble and used the paper to write it. I’m having a surprisingly hard time thinking of any documents out of the hundreds of thousands that I have read in wartime archives for which that is not true. Even the most seemingly neutral bureaucratic records, such as number of trains that went through a station, could have been falsified for various reasons.

But that is a level of research that is not likely to come up in looking for your own family’s history, so let’s take a much more obvious example.

In 1945 a young woman wrote that her husband, who died in the concentration camps, gave away his fortune to help Engelandvaarders escape. But just because she says it does not make it true. You have to ask yourself a number of questions.

The first asks about the context of the report. Why did she write it and for whom? Was it in her private diary? Was it a letter to a friend? Was it part of a legal claim to have the money returned to her from government funds? In short, does she have anything to gain from this claim? Obviously, if the government reimburses her for the money she says that her husband gave away, she has a lot to gain. I’m not saying that Read the rest of this entry »

When Was the Document Written?

Let’s continue our discussion of how to evaluate historical documents. In order to answer the question of who wrote the document and what his or her agenda may have been, you also need to know when the document was written.

In the case of the Second World War, the closer to the event a document was written, the more reliable it is. You might think that documents would get more reliable with time because more information would have been available, but they are not.

In 1944 and 1945, when the war was still happening, people reported what they themselves knew to be true. They may have been mistaken and emotions ran high, but they reported the truth as they saw it. Everything had happened recently enough that the community of witnesses kept each other honest. Plus the police and other authorities were checking people’s facts.

But things got swept under the rug in one way or another pretty quickly after the war. Every government in Europe promoted a particular myth about what had happened. Books were published that established the official history of events. Cultures developed Read the rest of this entry »

Who Wrote the Document?

In the last post I talked about the importance of knowing the context of any historical document. You also need to ask three key questions about any documents: who wrote it, when and why.

Who wrote the document? You need to know this to judge whether the author can be expected to (a) know the truth and (b) tell it. Very few people knew the entire story about any resistance action during the war for the obvious reason that it was a dangerous secret. But that does not mean that different individuals did not know different parts of the story.

Obviously, if you are reading the records of a purge trial in which a policeman was likely to be sentenced to death if he was found guilty for turning resisters over to the German police, you would not trust what the man said. What about the testimonies of the witnesses? They are more trustworthy, but they are not necessarily Read the rest of this entry »

How to Evaluate an Historical Document

A friend has asked me for some advice on how to research his family history during WWII. I know that there are a lot of people trying to piece together how a relative escaped Nazi occupation or served in the Resistance, so I’ll share these thoughts with all of you. I’ve already mentioned useful archives in other posts, so these will be about the method of research.

The most important thing to keep in mind about any document from the war is context. You need to know who wrote the document, when and why. And you need to understand not just the context of the time but of the particular document. It is not enough to find a page of a document on the internet or to rely on a single report.

No one writes things down, especially during a paper shortage, without a reason. The reason might be to convey family news to a relative in another town or country. It might be to file a missing persons report in the hope of finding someone who was arrested. It might be to accuse someone of collaboration or to make a case for the defense of the accused collabo.

All of these documents called for some sort of response and most of them Read the rest of this entry »